What a Century of Innovation Tells Us About the Future of International Education (Part 1)

Dev Srivastava

Jan 30, 2026

A few months ago, we were asked to present our views on the potential use of AI within the higher education ecosystem and showcase our technology at the AIRC 2026 conference. While I had often mused about how AI and other technological advancements would shape admissions technology in the coming years, here was the opportunity to present our beliefs to a larger audience. While discussing with our team, Tanmay, our co-founder at Trential, suggested we should situate it within a historical context. And it struck a chord with me.

At a time when the idea of adoption of AI introduces an equal mix of excitement and fear within communities, we seldom situate it within the larger and longer-run context of never-ending evolving technologies, institutions, and practices. It is quite natural that international education and the ecosystem enabling it would have gone through a similar evolution. What began next was a search into how various trends – political, geopolitical, economic, and technological – have interacted over the past century to produce the current behemoth of an ecosystem supporting international education, spanning universities, governments, testing agencies, credential evaluators, ATSs, CRMs, SISs, SEVIS, recruitment marketers, consultancies, and so many more.

While the US education community remains on edge with these uncertain times, it is comforting to see how our predecessors have faced similar anxieties and innovated through them, fueling growth for all. This two-part series explores the history of international education over the past century and makes predictions on the directions the industry will take in the coming decades.

In Part 1, we'll trace the evolution from the World War II era through today's digital transformation. Part 2 will focus on where we're headed: the dual tracks of AI solutions and verifiable credentials that will define the next two decades.

The WW-II World (1925-1945)

This period was largely dominated by World War II and associated dynamics. While some standardization was in progress for the higher education sector with the introduction of the SAT in 1926, the period was remarkable for the exodus of European talent – from the sciences to the liberal arts – to the United States, as they escaped war-torn Europe. The ensuing benefits might have been the key reason for the institutional policy encouraging students from abroad to study in the US in the subsequent decades after the end of the war, for cultural, scientific, and economic reasons.

Post WW-II Policy Changes and Institutionalization (1945-1975)

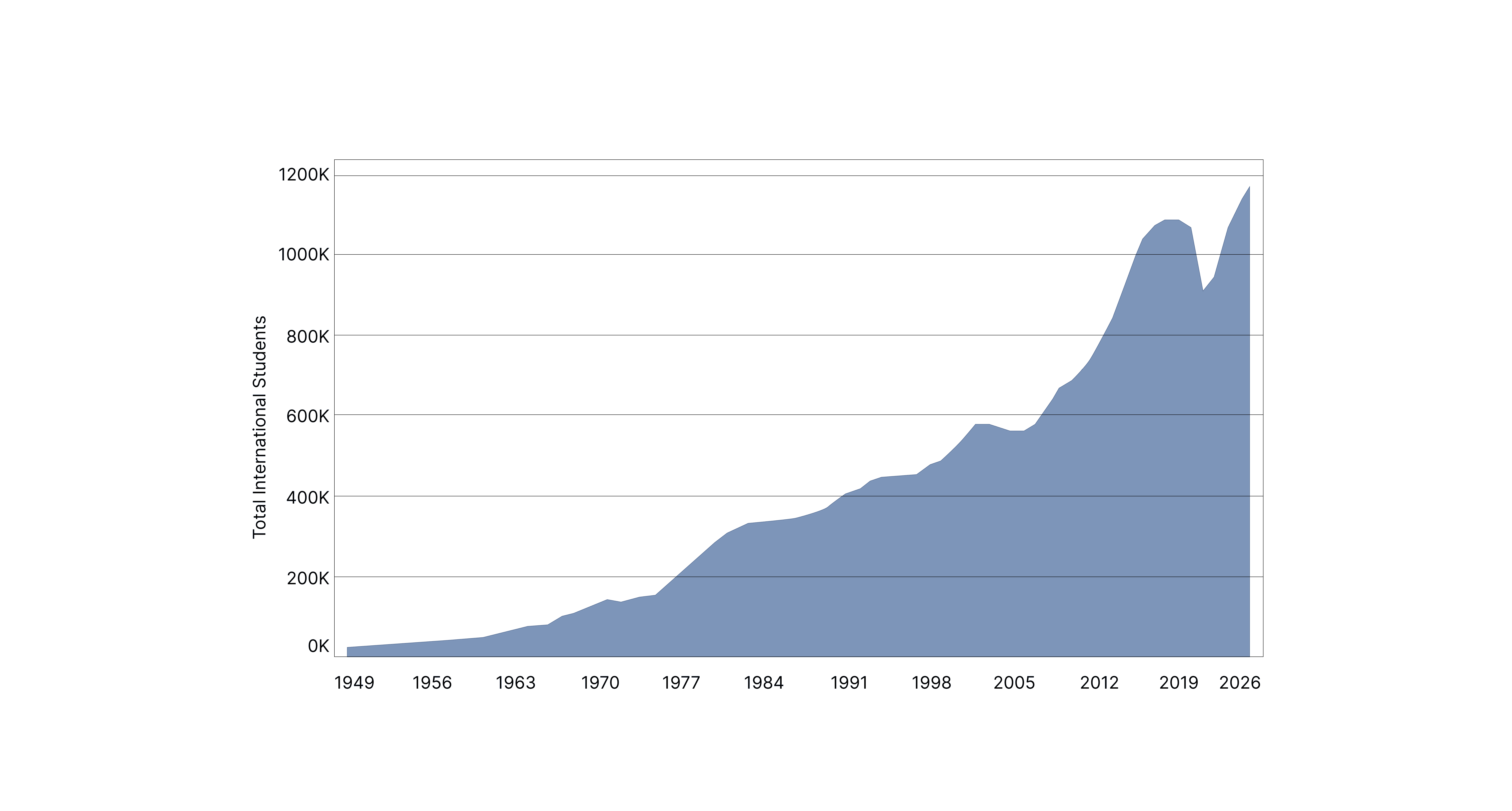

The decades following the war saw international education transform from an ad hoc arrangement into a formal system. In 1949, there were just 26,000 international students in the United States. What followed was a remarkable series of policy changes that would shape the landscape for generations to come.

The 1952 Immigration and Nationality Act formalized non-immigrant visa status for students, creating the legal framework that would allow millions of students to study in America. The early influx was driven largely by Cold War-era cultural diplomacy. The Fulbright program, founded in 1946, became a cornerstone of this effort, later strengthened by the 1961 Mutual Educational and Cultural Exchange Act (Fulbright–Hays Act).

But it was the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act – the Hart-Celler Act – that truly opened the floodgates. By abolishing national origin quotas, it opened US campuses to many more students from Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. The 1966 International Education Act further cemented this commitment, enacting federal grants to support international studies at American colleges and universities.

As total foreign enrollment began to climb more steeply, the need for specialized institutions, services, and standardizations became apparent. The first TOEFL was administered in 1964, giving universities a standardized way to assess English proficiency. IERF and WES were founded in 1969 and 1974 respectively, establishing the credential evaluation industry that would become essential to processing international applications. These policy changes spurred a dramatic surge in international students, requiring new institutions capable of handling the increasing inflow.

Early Web and Internet Boom (1995-2005)

By 1995, international student enrollment had reached 450,000, and the internet was about to revolutionize everything. CollegeNET launched its ApplyWeb® system for online admission application processing and evaluation, moving the process from mailrooms to servers. The Common App went online in 1998, and suddenly students could apply to multiple universities with a few clicks rather than multiple envelopes.

Testing followed suit. TOEFL was computerized in 1998 and migrated to an internet-based format by 2005, making it easier to administer globally and return scores faster. In 1998, WES launched its Automated International Credential Evaluation System (AICES), a database with digitized archives of country profiles and credential templates to speed the comparability of foreign qualifications.

The first education-specific CRMs started appearing during this period – Slate in 2001, Hobsons, and Salesforce Education Cloud – giving universities powerful new tools to manage their recruitment pipelines. With PDF uploads replacing hard-copy dependency, universities adopted web-based portals for applications, document submission, and payment of fees.

Then came a watershed moment: SEVIS became mandatory in 2003, pushing institutions to maintain accurate electronic records of international students. The SEVP to DSO to SEVIS to I-20 pipeline meant that compliance was no longer optional, and digital record-keeping became essential.

But with these advances came new complexity. Institutions were now juggling multiple systems, creating an urgent need for interoperability, data security, and compliance audits. The infrastructure was being built, piece by piece, even if it didn't always fit together seamlessly.

The Digital Transformation (2005-2025)

By 2005, enrollment had reached 565,000 international students, and the pace of change only accelerated. Universities migrated from siloed systems to integrated CRMs and applicant tracking systems. There was an explosion of APIs and batch feeds: test score APIs from ETS and College Board, CRM-to-SIS integrations, and the adoption of new data formats like XML and EDI.

Large-scale document scanning and digital repositories were developed, and universities adopted online transcript services through PESC standards by 2010. Professional networks like NAFSA, AACRAO, CIEE, and AIRC proliferated, offering training and data on international admissions and student services. Organizations like NACES and AICE continued to refine standards for credential evaluation.

Enrollment management evolved into a science. Universities hired specialized officers for international recruitment and data analysis, often informed by Open Doors reports and Campus International Student Office data. Digital credential platforms appeared: Parchment, Digitary, MyeQuals in Australia and New Zealand, CHESICC in China, and the National Student Clearinghouse in the US.

Systems now talk to each other, setting up the conditions for automation and data-driven decisions. "Digital-by-default" has become the expectation. Yet despite all this progress, most data entry by students and admission officers remains manual. Verification workflows require multiple manual checks. And a new challenge is emerging: increasing fraud, enabled by AI.